Command Line and the Shell¶

Command line interface (CLI) and graphic user interface (GUI) are two different ways of interacting with a computer’s operating system. The shell is a program that presents a CLI which allows you to control your computer using commands entered with a keyboard instead of controlling graphical user interfaces (GUIs) with a mouse/keyboard combination.

A shell allows simple interactive computer programming sessions that follow the REPL paradigm. In REPL, which stands for read-eval-print loop, the computer displays a prompt that is ready to take user's text input, waits for CR (Return) that indicates that the user finish the input, executes it, and returns the result as text as well, many times right after user's text, prints the prompt and awaits for the next input.

A program written in a REPL environment is executed in a piecewise, sequential manner: the computer does not start working on a command before it finishes the previous one. REPL's facilitate exploratory programming and debugging because the programmer can inspect the printed intermediary results before deciding what expression to provide for the next read.

The text that is typed by the user in a shell is made of short words that have simple meaning and are limited to well defined operations. By combining simple commands, your work can be done more efficiently and more quickly, than by using graphical interfaces that can present only a limited number of options and possibilities in menus and buttons that are cliked with the mouse. When you need to do things tens to hundreds of times, knowing how to use the shell is transformative.

Because is simple text that can be typed with a keyboard, CLI interaction is effective across different OS's and environments, allowing the use of remote computers or cloud computing.

There are many reasons to learn about the shell. For example, when you have to repeat a procedure it is might be hard and boring to remember the correct and precise succession of clicks and menu choices. Instead you can record the actions in shell script, and repeat it a thousand times with no mistakes. The shell makes your work more reproducible, and allows you to keep clean logs and records of your work.

How to access the shell?¶

On a Mac or Linux machine, you can access a shell through a program named Terminal, which is already available on your computer. In Windows, the situation is a little bit more complicated; the original shell has been a part since the MS-DOS era, even before Windows GUI, with a limited and slightly different set of commands. Open the search box and type the command cmd to run this shell. A Powershell program was later introduced to address the deficiencies of MS-DOS command shell. The newest versions of Windows 10, has yet another shell called WLS (Windows Subsystem for Linux) that behaves almost identical with a Linux one.

You can access a shell right from a Jupyter session from File > New > Terminal. You should see the prompt showing the current user and machine followed by $ and a blinking cursor indicating the shell is ready to accept text from you. The server that hosts Jupyterhub runs Linux and the specific shell that is available is called bash (Bourne Again Shell), a member of a large family of variants: ksh, csh, zsh, etc.

Let's see something simple. Open a terminal and type date

(base) [vrinceanu@node-1 ~]$ date

Wed Jan 27 23:58:03 CST 2021

(base) [vrinceanu@node-1 ~]$

Obviously, the command date here prints the current date and time and gives you another prompt, right after finishing printing the output.

Shells have a number of registries, or variables, that can be modified to allow various behaviors. For example, if you want to change the text of the prompt, you need to work with the environmental variable PS1. Type echo to see what is the current value, and change it to a simple \$ followed by space, and press ENTER

(base) [vrinceanu@node-1 ~]$ echo $PS1

(base) [\u@\h \W]$

(base) [vrinceanu@node-1 ~]\$ PS1='$ '

$

Note that the you need to use \$ before the name of the variable to obtain its value, otherwise the echo command would print just the word PS1.

Are you in an existential crisis? Try the command whoami

$ whoami

vrinceanu

There is a command for everything. The command hostname will tell you the name of the machine that takes your commands. The command cal will print a calendar. Are you in mood for a fortune cookie? Type fortune. Try it! If you are still not convinced about the power of the shell, type this: [ where is my brain?

The Filesystem¶

Data files, logs, libraries, manuals, binaries, are all stored in a hard drive. A modern computer has hundreds of thousand, and maybe millions of individual files. Bash, by design, is very efficient in understanding and facilitating operations with the filesystem in the computer.

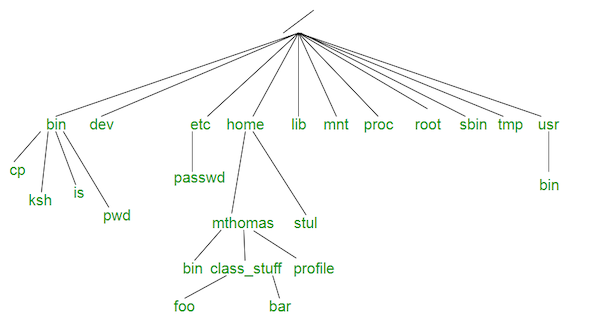

In Linux (as well as in a Mac, or even Windows) files are organized in a tree structure with branches, called directories (or folders), and leafs that are the actual files. The very top of the filesystem directory tree is called the root directory and is symbolized by "/". To arrive at a leaf, one needs to give a recipe of traversing the tree branch-by-branch starting from the root. Each directory name is followed by the character "/" to form the path to a file. Note that this is different from the backslash "\", used in Windows to separate folder names.

For example, the executable file for bash itself is locate here:

$ which bash

/bin/bash

$

In order to operate correctly, Linux expect a certain filesystem hierarchy includes folders like: /bin/, /usr/, and /var.

Every command is executed in the context of a current working directory. The command pwd (print working directory) will give you the precise position within the tree where you operate. By defaults, you have allocated a portion of the filesystem for your own use, which is a sub-tree that starts from your home directory.

Files in the current directory are listed with the command ls. An empty file is created with the command touch. For example:

$ touch new_file.txt

$ ls

It happens that I have a lot of files in this directory. It is better to try

$ ls new*

This will list only files that start with new, the star symbol "*" is special in a shell and it means any sequence of zero or more characters. Let's see what is in this file:

$ cat new_file.txt

$

Of course, the command cat (concatenate) returns nothing because the file is empty. Let's dump some numbers in it:

$ echo '1.0 3.1415926' > new_file.txt

$ cat new_file.txt

1.0 3.1415926

$

This example illustrates one of the magic tricks that makes the shell super-powerful. You can pipe the output of one command to the input of another. The symbol for that is ">".

The command mkdir makes a new directory within the current one. The command cd changes the current directory

$ mkdir new_directory

$ cd new_directory

$ ls

$ ls -al

total 8

drwxrwxr-x 2 vrinceanu vrinceanu 4096 Jan 28 01:17 .

drwx------ 93 vrinceanu vrinceanu 4096 Jan 28 01:17 ..

The brand new directory does not have any files, we just created, but it is not actually empty. We use ls with option (or flag) -ls to see the files that could be hidden because the start with ".". The two elements elements here have special meaning for the shell: "." refers to the current directory, while ".." refers to the parent directory. cd .. would simply go back one branch in the tree.

Using '-al' options also gives a lot more details about the files, like ownership, access permissions and creation time.

What other options are available for the ls command? One can simply use the "help" option '-h' for a summary of options, or use the manual command man for a detailed and complete explanation.

$ ls -h

$ man ls

There are manual pages for hundreds and hundreds of commands, you don't have to memorize them. Each manual entry can have many pages, one navigates from page to page with the bar space, and quits the manual and returns to the shell with q.

Shortcuts and tricks¶

Typing out file or directory names can waste a lot of time and it’s easy to make typing mistakes. Instead we can use tab complete as a shortcut. When you start typing out the name of a directory or file, then hit the Tab key, the shell will try to fill in the rest of the directory or file name, or give you suggestions.

$ cd ..

$ cd new_<tab>

new_directory/ new_file.txt

$ cd new_directory/

The shell will fill in the rest if you've typed enough characters to provide a unique identifier for the file or directory you are trying to access.

The shell remembers all the commands that you type. If you press arrow up ⇧ or arrow down ⇩, you can recall any previous command from the history of commands.

Some files are binary and can be executed. They can be native commands that came with the OS, created and compiled by other programmers, or created by you. When typing a command, the shell first looks for an executable within the current directory. If it can not find it there, then it looks in set of special directories that are stored in the environmental variable PATH. Type echo $PATH to see what is available. There maybe useful commands stored in other directories, if those directories are not listed in $PATH$, then the only way to run those programs is to navigate with cd to these places. The other option would be to augment the PATH variable with the new path

PATH=$PATH:\path\to\the\special\directoryWarning: The new PATH will take action immediately, so you can use the command from anywhere, but will not be available the next time you log into the shell, unless you place this command into a special hidden file called .bashrc in your home directory which gets executed every time to start the shell, locally or remotely.

If type just cd, the shell will put you directly into your home directory no matter where you are in the filesystem. You change the directory by using a relative path like in cd new_directory or an absolute path by starting from the root cd /home/vrinceanu/new_directory. There is yet another way to get to your files by using the special symbol ~ which represents your home directory. So will obtain the same result with cd ~\new_directory.

A stubborn program can be stopped with Ctr-C, or, many times can be exited with Ctr-D. You can copy a file with cp, move (or rename) it with 'mv`, delete (remove) it with 'rm'. Here I remove a whole directory, all files and directories within

rm -rf new_directory/*

Warning: The command rm is extremely dangerous since it removes the files permanently. Can you guess what happens if cd /; rm *. Your whole world would be destroyed. DON'T try it!

Using Python from the shell¶

Python itself is a command that you can run from the shell, works like a REPL, and in many respects works exactly like a more powerful shell. The most basic way of using it is to type python. Python will normally display some information and then return with a new prompt >>> to indicate that you are not in the shell anymore, and that you can type a Python command.

$ python

Python 3.7.6 (default, Jan 8 2020, 19:59:22)

[GCC 7.3.0] :: Anaconda, Inc. on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> print("Python rocks")

Python rocks

>>> 32*43

1376

>>>

$

As usual, hitting Enter will execute the command you typed and return >>> when is ready for the next command.

As you can see, Python can be used as a quick calculator. You dismiss Python with Ctr-D in Linux and Mac, or Ctr-Z in Windows, and return back to the shell.

Commands can be recorded in files and executed on demand. Suppose I have a homework problem that says:

"Calculate the elevation of a tennis ball 1.2 seconds after is launched vertically straight up with 7.3 m/s."

Can Python help? Sure! Here is how I do it from the comfort of CLI and bash:

$ cd ~/my_working_pad/physics_class

$ echo "v0 = 7.3" > homework.py

$ echo "g = 9.8" >> homework.py

$ echo "t = 1.2" >> homework.py

$ echo "y = v0*t - g*t**2/2" >> homework.py

$ echo "print(y)" >> homework.py

$ python homework.py

1.7039999999999997

First I neatly carve a space where I can carry my work, and change to that directory. I create the source code by piping the echo command to a file that ends in .py. It does not have to be like that, but in 2 month I will be glad that I did because I will remember why I created that file. It contains Python code. Note that I used the simple indirection > the first time, and double indirection >> after that. This is because the simple > creates a new file or destroys the content of the file, if it existst, before dumping the text in it. The double >> preserves the content of the file and appends the text to the end.

Of course, I could have use a text editor for writing the files, but here it is just quicker to do it like this.

Warning: Python is a little quirky when it comes to mathematical operations. For instance the square is NOT obtained with ^ symbol,as you may expect, but you have to use double star **.

Finally, I execute the file with python name_of_input_file.py and get the result printed on screen. Homework done. And documented for eternity!

Exercise: Create a new text file in Jupyter (File > New > Text File), type the above python code and save it as "homework1.py". Execute the script from the terminal.